The Q&A Series: Rachel Laudan

/Welcome to the Q&A series, a project aimed at examining food politics and the "food debate" through the eyes and minds of people involved in making and thinking about food. My questions are in bold; the interviewee's responses are in plain text.

Today's guest is Rachel Laudan.

____________________

Rachel Laudan is a historian of food, culture, and science living and working in whiche ver country she happens to be living in at the moment (the list is long). She’s the author of, among other things, Cuisine and Empire: Cooking In World History. You can find her at rachellaudan.com

Courtesy of Rachel Laudan

_____________________

Q.: After I read an interview with you from the Rambling Epicure, I wanted to call my publisher and say “STOP THE PRESSES. Don’t publish the meat book! It’s crap! I’m going to study with Rachel Laudan for ten years and THEN I’ll write about meat.”

Which is to say: I admire the way you analyze food and history and the way you link both to the history of technology. (My Ph.D. is also in the history of technology, which I gravitated to because it seemed like the perfect framework on which to hang just about anything.)

But as you know, the blessing and the curse of the historian is that we examine everything from the long-view/big picture perspective. As a result, the “food debate” here in the U.S. provokes a whole lotta eye-rolling on my part. (And although your perspective is global, here I want to focus on the U.S. because that’s my area of expertise and interest.)

To that end, I framed this Q&A by “borrowing” some of what you said in the Rambling Epicure interview.

The Rambling Epicure interviewer asked you “What holds a cuisine together?” and you replied “systems of belief or ideas or culture.”

There it is, in a nutshell: All the chatter about local food versus not; organic v. processed; “family farms” v. “Big Ag” and “Big Food” is just that --- chatter. None of it addresses fundamentals.

In the specific case of the United States, we’ve got “Big Ag” and “Big Food” because a century ago, when the U.S. economy shifted from agrarian to industrial, Americans favored an agriculture and a food-making system served the needs of a population that was increasingly spread out physically (it’s easy to forget just how much land the U. S. covers) and that was urban (city folks don’t produce their own food; an urban society requires efficient agriculture so that a small minority can feed an urban majority).

The agriculture/food system that Americans began building then dovetailed with a prized cultural value: efficiency, of which the factory was the premier example. So over the past century, we Americans have refined a method of agriculture/food-making/food retailing and delivery that mimics the factory’s efficiency. Yes? No? Maybe with caveats?

A.: I think I’d put it slightly differently. Since the land was the chief source of wealth until very recently, those who owned the land always tried to exploit it as efficiently as possible. We tend to think of a past of peasant or yeoman farmers on small farms growing food for their own consumption with a little extra to sell.

But in fact agriculture has been big since very early on. Think of the vast effort put into underground irrigation channels by the ancient Persians, the ancient Greek reform of methods of growing vines, the large Roman vineyards, the terracing of rice paddies, the draining of the Dutch polders, and so on.

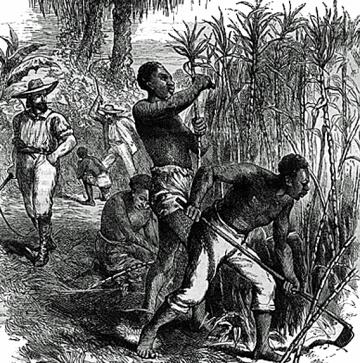

And to come back to the United States, which is the focus of this discussion, for all the acres belonging to yeoman farmers, there were other big farms in the hands of large landowners, notably plantations. As you well know, many historians see plantations as pre-figuring industry in their organization of labor, say. In fact, I always found it interesting that the earliest iron extraction in the United States was organized on the plantation model.

So, no, I do not see agriculture mimicking the factory’s efficiency. I see the farm as possibly leading factories but at the very least changing in parallel.

And let me make it clear, this is not to attack farming but to praise it. I think it is good to be efficient.

Q.: But that assumption means, of course, that the ONLY way to reform our food system (assuming it needs changing) is by building one that matches our “values.” But it strikes me that a primary “value” in contemporary American society is that of maximal “individualism.” We have no core set of values except a value system rooted in “we want what we want and the rest of you be damned.”

So how exactly can or does reform work? I mean, I don’t know about you, but if the Pollanites get their way, we’re gonna need a whole lot more farmers than we have now to manage all those small, labor-intensive, pasture-based farms. I’m not volunteering to “move to the countryside.”

A.: Hmm. There’s a lot going on in this question. Although you ask about the food system, your focus is on farming so I will restrict myself to that, although I feel more comfortable with food processing. Like you, although I think our agriculture now, as in the past, needs constant improvement, I am not convinced that it needs to be abolished and made over.

I am less worried than many of my contemporaries, for example, about large-scale commodity farming. Farming has never been just about the production of food (which is why the description of the farm bill as the food bill is so misleading). It’s also about the production of all kinds of raw materials for the society, including fiber, fuel, building materials, etc. etc. We need all the economies of scale we can muster.

Of course, farming has its problems just like any production system. But farmers themselves have a huge vested interest in solving those problems so that they can hand on productive land to their children, be seen as stewards of the land, and save money. And improvements are being made all the time. Look at how much more efficiently fertilizer and pesticides are now used. Look at the huge strides being made in precision farming. Look at the whole debate over animal welfare.

And of course, I think it’s important to have small farmers entering the system just as it is important to have small businesses entering the system as an alternative source of new ideas.

But do I see a large-scale move back into farming? No.

Q.: In that vein, my greatest frustration with the “food movement” is that its advocates resolutely ignore a fundamental issue: City people don’t make their own food. They rely on farmers. Over the past nearly two centuries, Americans have made it abundantly clear that they prefer city to country. (Thanks to urbanization, Steve Jobs, for example, could focus on inventing cool stuff because he didn’t have to spend his days pulling weeds and canning food.)

Because we Americans prefer city to country, we have --- we MUST have --- an agriculture and a food-making system designed so that a tiny minority can make food for an enormous majority.

Is that too simplistic a view? And given that demographic and geographic reality, how could we engineer the cultural changes necessary to successfully feed people with what amounts to a retrogressive system of food production? (Bare minimum, we’d have to raze all manner of urban structures and return that land to farming. And then we’d have to persuade people to move to farms.) (N.B.: I’m NOT volunteering.)

As I said, I don’t think it likely that there will be a big move from urban occupations to farming. People enjoy having a choice of what to do with their lives. (But I’m not sure that even if it happened, it would be necessary to raze urban structures. The US has plenty of land to feed itself and to make a good income exporting as well).

Q.: A related and perhaps more important matter is the current state of “science.” You started your career as a historian of science, so I’m sure you have an informed opinion about the loss and politicization of scientific authority. And without science as an authority, who/what is our society’s “authority” for making policy and decision?

Should science even be part of that? I’m thinking specifically of hot topics like GMOs and whether “organic” food is healthier than non-organic. There are no clear answers, or at least no answers that people agree about. Indeed, in many respects the entire “food debate” is a struggle to control knowledge.

Yes, this is a question that interests me a lot. And I am not sure that there was a golden age of scientific authority.

Before I turned to food history, I was writing a book that I want to go back to. It dealt with all the arguments that scientists have made in the past three hundred years to convince their publics (which have varied from royal households to democratically elected bodies) that science should be funded and should be the authority about the natural world, including our own bodies and health. They have always been in competition with other claimants ranging from rhetoricians and alchemists to practitioners of alternative medicine.

And as you know, there is a considerable literature on how to reconcile the often-recondite knowledge of science with democracy. I think science must be central to policy making and decision. But I don’t think it can be by the stamping of feet and asserting authority. I think it must be by constant efforts both to made scientific research accessible (popularization) and to explain how science works.

In the past, the explaining of how science works was taken up by senior scientists (statesmen of science) who responded to the appearance of new sciences, first the mathematical sciences, then the natural history sciences, then the experimental sciences.

No one has come forward in that role in the last fifty years. And more’s the pity because so much science now, especially science relevant to food production and consumption, including the sciences that deal with climate change and health and nutrition, rely on big data and its statistical analysis. And that needs to be clearly explained. So too does the whole question of scientific error, false positives and negatives. There’s an excellent article on that in this week’s Economist.

Q.: A related question: As you know, food reformers lay the blame for our entire food system at the feet of “capitalism.” In their worldview, “capital” and “capitalism” are real things with autonomy that have power and force and are causal mechanisms. Where do you stand on that?

Is it capitalism? Or corporate capitalism? I don’t really have a stand except to say that the position seems to be a tad incoherent.

As many have pointed out, it seems odd to take advantage of the internet, the i-phone, and the jet plane while arguing for a yeoman agriculture. I would favor working with corporations not trying to get rid of them. When I was doing the research for Cuisine and Empire, I was fascinated to see how many farming and food processing innovations were disseminated by earlier corporations (aka monasteries or religious houses), whether Buddhist, Islamic, or Christian. Try irrigated rice, sugar, tofu, tea, coffee, water mills, and vineyards.

The more interesting critiques I have seen argue that new technologies ought to allow us to get away from large-scale farming or processing. And they may. And that might be desirable in some cases.

But small scale enterprises are highly vulnerable to economic downturn and to problems of inheritance. I believe I am right in saying that it was small scale farms that were most vulnerable (and therefore did the most damage) in the Dust Bowl. Certainly small scale farms are no insurance against ecological damage as thousands of years of small scale agriculture show. And think of the problems of family businesses when the time comes to replace the founding member.

Q.: Back to that interview with Rambling Epicure. You said:

History is my way of understanding things. A lot of food writing is about how we feel about food, particularly about the good feelings that food induces. I’m more interested in how we think about food.

For example, historians of technology are not primarily concerned with inventions. The infamous light bulb was useful only as part of a whole electrical system.

Similarly soy sauce, say, or cake, have to be understood as part of whole culinary systems or cuisines. When these are transferred, disseminated, copied, they change the world.

And, perhaps most important, new ideas or values prompt cooks to come up with or adopt new techniques. Technology, including cooking and food processing, is a problem-solving activity and people bring to it their ideas. If people change their minds about what healthy food is, or adopt new religious beliefs, or reject monarchy as a political system, cooking and dining change too.

Can you translate that systems perspective into a specific case or example as related to the current food debate? We seem to be living in a moment of exceptionally intense cultural transformation (because of digitization). Is that why there’s such an intense debate about food: Our fundamentals are in flux and food is a fundamental?

(And as an aside, no surprise, I used the lightbulb example in the meat book to explain how/why Gustavus Swift succeeded where others failed.)

A.: Well, I recently saw a nice example of the necessity of a systems approach for those who want to reform farming. I don’t remember the details but the situation was basically this. In order to have organic meat or milk, you have to have organic feed for the cattle (lovely as pasture is, grass doesn’t grow for much of the year). And those in the production of animal feed did not find it economic to produce organic feed. And thus livestock farmers couldn’t get the feed to keep their operations organic.

I am not sure why there is such an intense debate about food. If I had to guess that the causes are basically the same as it was with earlier counter cuisines.

(1) Food becomes us as it is assimilated to the human body. If we are dissatisfied with the state of “us,” then changing eating habits is a way to express that dissatisfaction.

(2) Food is the product of a particular political/economic/social/religious system. If you don’t like that system, then you will want to change your food. Americans, for example, rejected the monarchism of Europe and thus they rejected the elaborate meals that monarchs ate to reflect and reinforce their distinctness from their subjects.

Q.: More than a decade ago, you wrote an essay arguing that we should praise rather than damn “processed” foods. You criticized what you labeled Culinary Luddites: People who favor local, pure, fresh, natural foods, and who avoid and condemn “processed” foods. Here’s a brief excerpt from that essay (which is available online in a condensed version here):

Culinary Luddism has come to involve more than just taste, however; it has also presented itself as a moral and political crusade --- and it is here that I begin to back off. The reason is that . . . [that] I am a historian. As a historian I cannot accept the account of the past implied by this movement: the sunny rural days of yore contrasted with the gray industrial present. . .

Certainly no one would deny that an industrialized food supply has its own problem. Perhaps we should eat more fresh, natural, local, artisanal, slow food. Does it matter if the history is not quite right?

It matters quite a bit, I believe. If we do not understand that most people [in the past] had no choice but to devote their lives to growing and cooking food, we are incapable of comprehending that modern food allows us unparalleled choices not just just of diet but of what to do with our lives.

You wrote that more than a decade ago, long before the virtues or failings of “processed” and fast foods had become weapons in the food debate (see, for example, David Freedman’s recent cover story for The Atlantic magazine). I’m guessing that your view has not changed. Or has it?

A.: Well, on processed foods, in a nutshell, I think all foods are processed, if by processed we mean “transformed from their natural state”. The proportion of our calories that come from “natural” foods is very small. Meat, milk, grains, sugar, vegetables are normally consumed only after chopping, grinding, pounding, evaporating, heating, and so on. That is true as far back in human history as we can go. It is true of even the diet of raw foodists.

So I think the debate should not be framed as one of non-processed versus processed but as one of good processed foods versus bad processed foods. And that turns out to be very complex because what counts as good has so many aspects: taste, health, cost, convenience and so on. Everyone weights these different values differently.

And it’s rarely that one food scores high on all. Sugar, for example, tastes good, is inexpensive, does wonderful things for cakes and cookies, but in excess is unhealthy. Spam, on the other hand, is a food source of protein and fat, lasts a long time, has been invaluable for hungry people but to Americans it does not taste good, brings back memories of bad times, and is, to say the least, déclassé.

So there are no quick answers here. But in many ways that is a cause for rejoicing, not for concern. For most of history, people were lucky if they got enough to eat. The choice was eat it or leave it.

Now we have the luxury of fine tuning what we eat to the values we believe to be most important. It’s more complicated, it’s a responsibility we have to ourselves and others, but also a huge privilege.

Q.: Finally (!) what do you think the American food system will look like ten years down the road? Fifty years out? Or is that even a fair question?

A.: Not the foggiest. Once of the things I learned writing Cuisine and Empire is that no one would have predicted the industrialization of food processing and the disappearance of famine in Europe within half a century in the 1840s; no one would have predicted the recovery of the food system so quickly following World War II. So I am not in the business of making predictions.

Q.: I lied. One more question: As a citizen and a consumer, what changes (if any) would you like to see in our food system?

A.: Not so much in the food system as in our thinking about food. We have unparalleled choice of food. That is a wonderful thing.

But we have a philosophy of food that dates from days of scarcity, the common condition of the human race until recently. And that philosophy is all about dictating what people should eat for their own good or for the good of society. I would like to see the talk of feeding the world change to talk of ensuring that the abundance we enjoy is extended to those whose choice, as I just said, is eat it or leave it.